Mathematics in Crisis

How decades of policy shifts and lowered standards have eroded student readiness—and what it will take to rebuild

Over the past three decades, U.S. mathematics education has undergone a series of well-intentioned but ultimately harmful reforms. Driven by shifting standards, political pressures, and a redefinition of “equity,” these changes have dismantled the placement systems, skill benchmarks, and instructional rigor that once prepared students for advanced study.

The results are measurable and troubling: declining performance on national and international assessments, a widening gap between top and bottom performers, and a generation of students advancing through the system without the foundational skills they need. Nowhere is this more visible than in California, where fewer than a third of high school juniors meet grade-level expectations in math.

The Vanishing Foundations

Once upon a time, students were placed in math classes according to their skill level. Algebra, geometry, and beyond had multiple tracks—allowing advanced students to fly while struggling students got targeted support. That’s largely gone. Today, everyone is pushed through the same course sequence, whether they’re ready or not (Brookings, Education Next).

The theory—“equity”—sounds noble. The reality is that high-achievers are bored, struggling students are lost, and nobody gets what they actually need. Teachers report ninth-graders arriving in class unable to add integers or multiply fractions, yet being promoted to higher-level math and science anyway (EdWeek).

Lowering the Bar

Grades have been inflated to the point of meaninglessness. In many districts, 80% is now an A, and 60% earns a B. In elementary school, homework and testing are sometimes discouraged entirely—making it impossible to know if students have mastered anything at all (WMAL).

Group projects are pushed over individual problem-solving, which usually means the most capable student does the work while everyone else coasts (Just Equations). Meanwhile, special education services have been scaled back, leaving students with learning challenges in general-ed classes without effective support—forcing teachers to water down content across the board.

How We Got Here

This decline didn’t happen overnight. In 1989, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics standards shifted the focus from procedural fluency (knowing how to do the math) to “conceptual understanding” and encouraged reliance on calculators (NRC/GT).

After backlash from parents and educators, California’s 1997 math standards reintroduced rigor—including a push for Algebra by 8th grade—which led to rising test scores and more students reaching AP Calculus (EdWeek).

But in the early 2010s, the Common Core State Standards reversed that trend. Backed by Race to the Top funding, the focus again swung toward “conceptual understanding” over mastery of skills. The California Math Framework now prioritizes “practice standards” (how students learn) over “content standards” (what they learn), emphasizing project-based learning and even social justice themes over procedural fluency.

The result? Many students can explain what they’re supposed to do but can’t actually do it. Multiplication tables and standard algorithms are downplayed—“Why memorize? That’s what calculators are for!”—and procedural skills have withered. Without fluency, complex problem-solving overloads working memory, impairing reasoning and deep understanding (Mind Matters).

The Data Speaks—Loudly

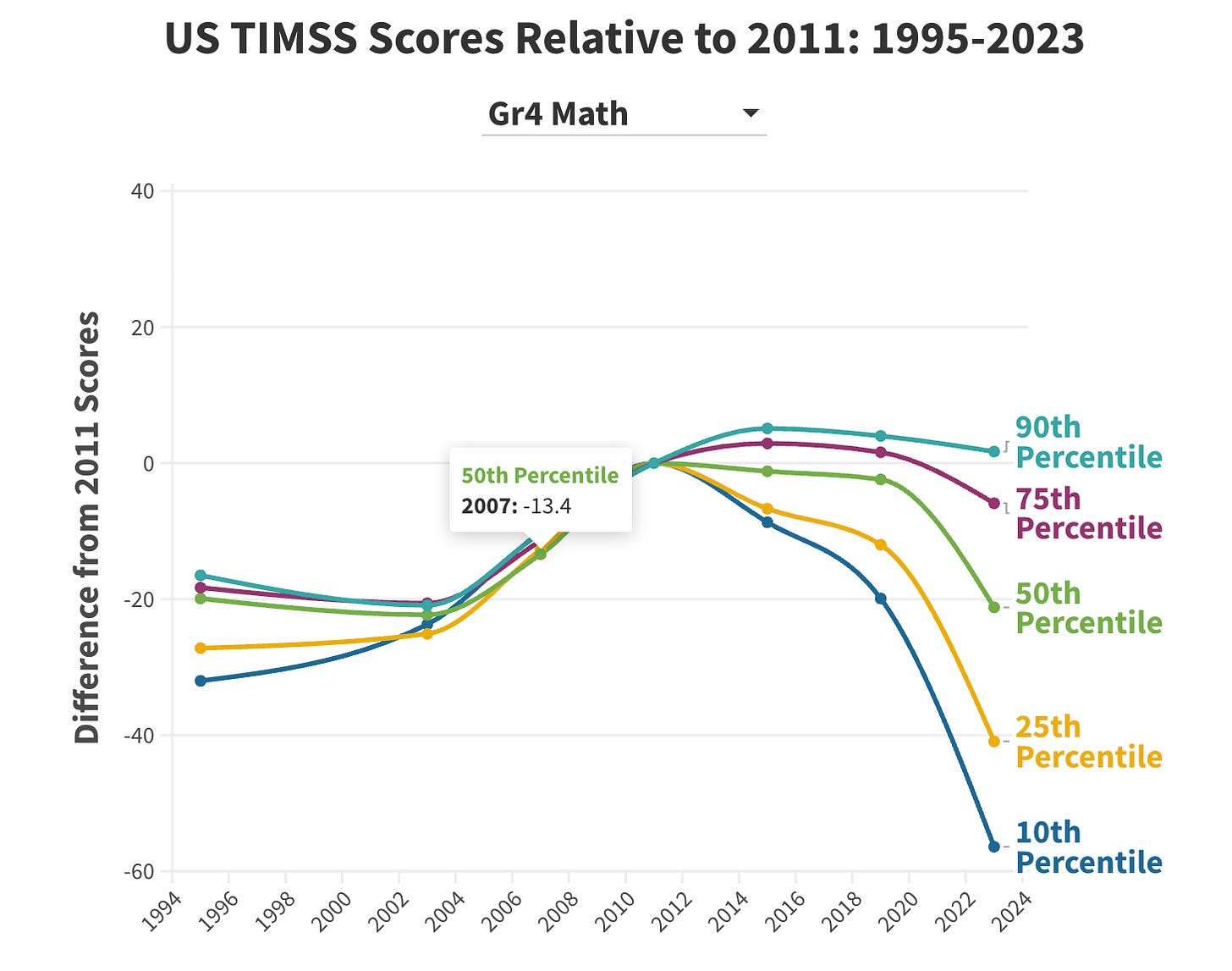

International benchmarks tell a similar—and in some ways more alarming—story. The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) shows U.S. Grade 4 math performance improving modestly through 2011, then diverging sharply. Since then, top-performing students have held steady while scores for lower-performing students have plummeted—especially after 2019.

This widening gap starts early—in California, fewer than 30% of 11th graders meet math standards, and the decline begins as early as third grade.

Globally, the U.S. is losing ground—countries like Poland, Sweden, and Australia now outperform us in areas where we once held an advantage (The 74). Within the U.S., the divide between top and bottom performers is widening. From 2013 to 2019, the lowest-performing students dropped an average of 7 points on national assessments while the highest-performing gained 3 (EdWeek). COVID accelerated this trend, with lower-performing students experiencing the steepest losses (Vox).

Why It Matters

Math is cumulative. Miss fractions in 4th grade, and algebra becomes a nightmare. Struggle with algebra, and calculus—and most STEM careers—become inaccessible. These policy changes don’t just affect test scores; they limit futures.

Equity doesn’t mean dragging everyone to the middle. True equity means giving each student what they need to thrive—which sometimes means different tracks, more practice, and yes, the hard work of memorizing times tables.

What Parents Can Do Now

If your child is in K–4, make sure they master addition, subtraction, multiplication, and fractions early. By middle school, ensure they’re on track for Algebra by 8th grade—most students who reach calculus in high school took that path. If your school won’t provide the rigor, supplement it yourself or with expert help.

At Cogito Learning Center, our tutors specialize in building strong math foundations and accelerating advanced learners—without watering down the content. We work with families who refuse to accept “just getting by” as enough. If you want your child not just to keep up, but to excel, reach out today and let’s chart the course together.

High school math is also not math.

Wow! I followed the link you provided to "Just Equations," and what I read there was ridiculous! The NCTM produced a report that said, "Tracking is insidious because it places some students into qualitatively different or lower levels of a mathematics course." What's insidious about placing students in classes in which they can handle the material? They tried to claim that tracking limits a student's opportunities, but it actually does the opposite. A child who is placed in a course that is beyond his current skill level will learn nothing. If he were placed in a course appropriate for his skill level, at least he would learn that material, even if it is at a lower level, at least it would be something rather than nothing.